Women's Identities at War by Susan R. Grayzel

Author:Susan R. Grayzel [Grayzel, Susan R.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Social Science, Women's Studies

ISBN: 9781469620817

Google: x0f1AwAAQBAJ

Publisher: UNC Press Books

Published: 2014-03-19T05:42:38+00:00

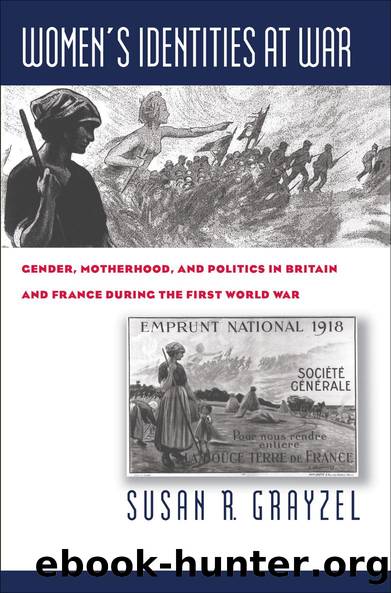

âHélène Brion in masculine costume,â photo that appeared on the front page of Le Matin, 19 November 1917. Courtesy of Association pour la Conservation et la Reproduction Photographique de la Presse, Paris.

The language and images used in the various accounts of Brionâs arrest suggest the importance of gender in her case. Other than the persistence of the accusation of âMalthusianismâ and her having some neo-Malthusian pamphlets, little evidence suggests that Brion was primarily involved with the birth-control movement. âDefeatism,â âanarchy,â âantimilitarismââthese terms merely proclaimed left-wing activity, but âMalthusianismâ took on a peculiarly gendered tone, a code word in pronatalist and particularly wartime France for the worst fears about feminism. By associating feminism with Malthusianism, the feminist could thus be attacked as refusing the most central and natural patriotic role for any woman: maternity. With the initial news of her arrest, Brion as a woman and as a feminist was on trial. The reproduction of her portrait labeled âin masculine costumeâ further illustrated the extent to which her âfemininityâ as much as her âFrenchnessâ was being called into question.81

While angrily condemning Brionâs harmful, unpatriotic actions and attacking her âfemininity,â the daily papers also emphasized her profession and attempted to separate Brion from other teachers. On 20 November Le Petit Journal ran an interview with a Mme. M., secretary to the director of schools in Paris, who described Brion as a âtemptressâ trying to enlist the aid of co-workers in her odious work. Although M. acknowledged Brionâs considerable intelligence and service, that she âloves the children,â she stressed nonetheless that Brion was âvery proudâ and âvery dangerous.â82

By the time Brionâs home had been searched and more damaging evidence uncoveredâin the form of pictures of Lenin and Trotsky and copies of âdefeatistâ literature and correspondenceâthe attention paid to her in the daily press had dwindled. Yet the cumulative portrait that emerged from this barrage of negative press was filled with contradictions. Brion was described as both hysterical and masculine, irresponsible and dangerous, tempting and hard, in other words, qualities loaded with both masculine and feminine connotations. Brion thus was blamed for both being ânaturallyâ femaleâa hysterical, irresponsible temptressâand âunnaturallyâ maleâmasculine, dangerous, unflinching.

These attacks, especially what was implied by the photograph of her in âmasculine costume,â quickly evoked a response from her supporters.83 In an article in LâHumanité on 20 November 1917, friends of Brion sought to correct misinformation printed in at least five Parisian newspapers.84 They charged that those interested in prosecuting Brion were permitted âto create in the public [mind] false sentiments and to establish a presumption of guilt. These proceedings are infinitely regrettable, above all because the facts thus insisted upon by journalists have not been verified.â85 Brion was the secretary of Pantinâs Workersâ Orphanage Society, and a petition was circulated by the society protesting both her arrest and the attacks made on her in the press. It called upon âwe who love her, we who have for her a high and deep esteem, a profound admiration, [to] not let her

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

On the Front Line with the Women Who Fight Back by Stacey Dooley(4332)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4152)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(3949)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(3760)

The Confidence Code by Katty Kay(3611)

Three Women by Lisa Taddeo(2939)

A Woman Makes a Plan by Maye Musk(2866)

Inferior by Angela Saini(2856)

Pledged by Alexandra Robbins(2810)

Not a Diet Book by James Smith(2770)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(2704)

Wild Words from Wild Women by Stephens Autumn(2619)

Nice Girls Don't Get the Corner Office by Lois P. Frankel(2618)

Brave by Rose McGowan(2523)

The Girl in the Spider's Web: A Lisbeth Salander novel, continuing Stieg Larsson's Millennium Series by Lagercrantz David(2399)

Why I Am Not a Feminist by Jessa Crispin(2268)

The Clitoral Truth: The Secret World at Your Fingertips by Rebecca Chalker(2268)

Women & Power by Mary Beard(2242)

Women on Top by Nancy Friday(2152)